Open Wiring

(2015)

Drawings, videos, sculptures, sound, and found documents

3-floor site-specific installation

In electrical systems, open wiring is a temporary method for distributing power. It’s fast and visible but exposed and vulnerable. Often used when infrastructure is damaged or time is short, it solves immediate needs while risking long-term stability. It’s a functional improvisation—resilient, but fragile.

This concept became the structural and metaphorical framework of Open Wiring, a multi-layered installation of drawings, videos, sculptures, sound, and archival materials.

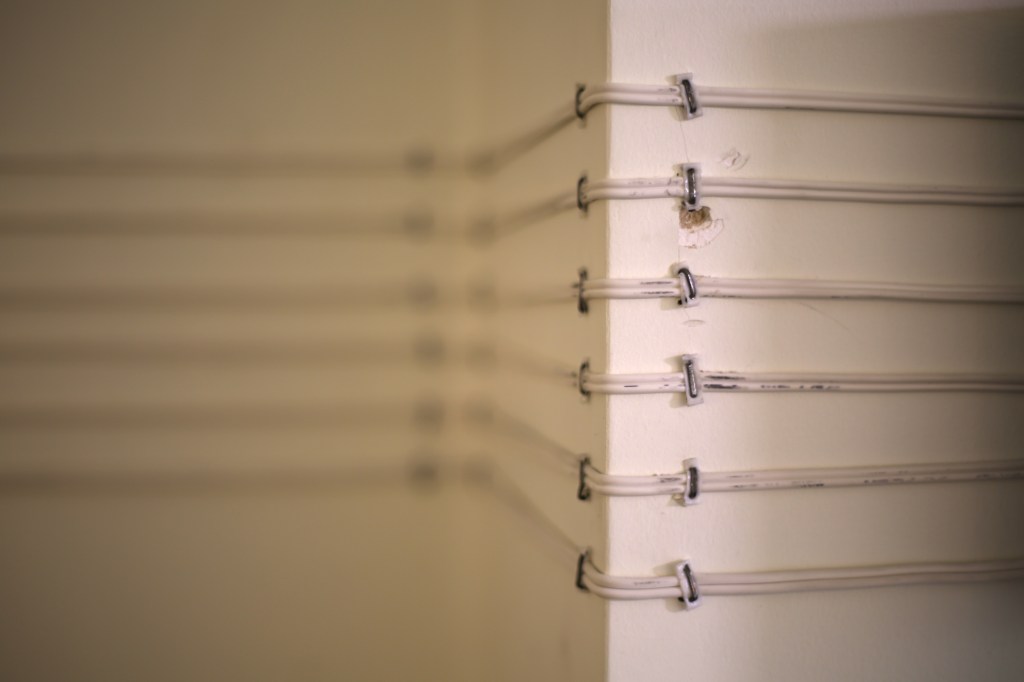

Spanning three floors of gallery space, the works were physically connected with cleats and visible cables that snaked across the walls, floors, and ceilings—inviting viewers to follow the wiring and trace unseen connections between seemingly unrelated elements.

The project presents a mental map of the artist’s thought process between 2009 and 2015. Like exposed wiring, it reveals raw, unfinished circuits of reflection. Some works directly relate to one another; others float independently yet are still charged with the same current of questioning. It’s a network of fragments rather than a linear narrative; space where short-term thinking, improvisation, memory, critique, and contradiction coexist.

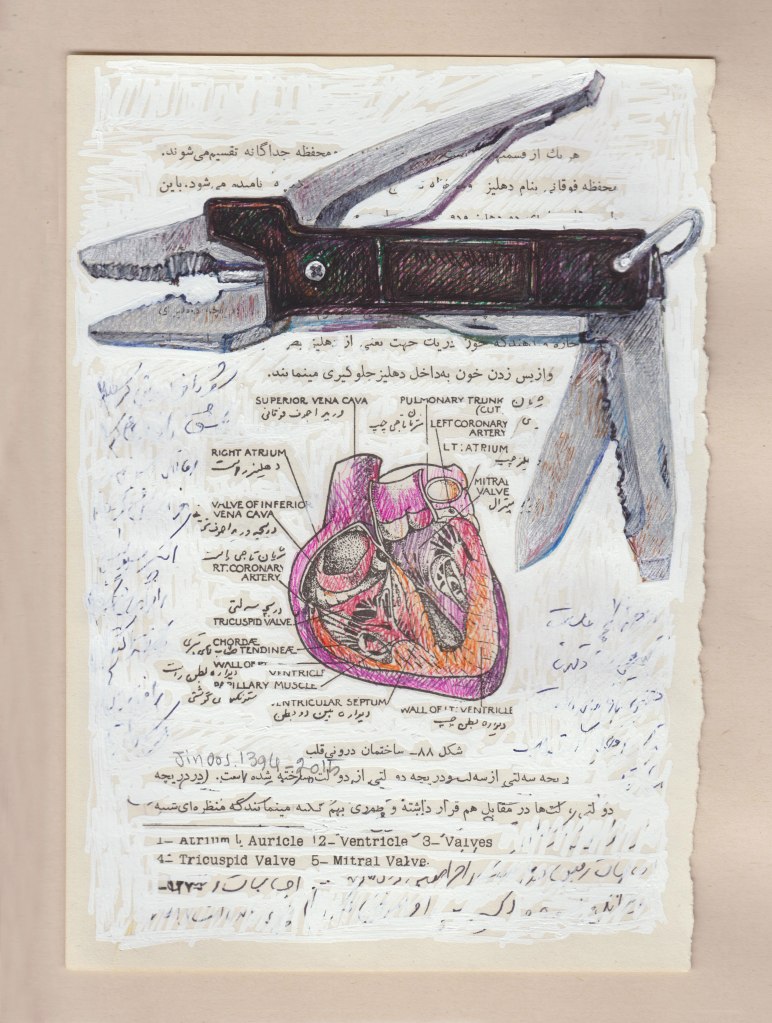

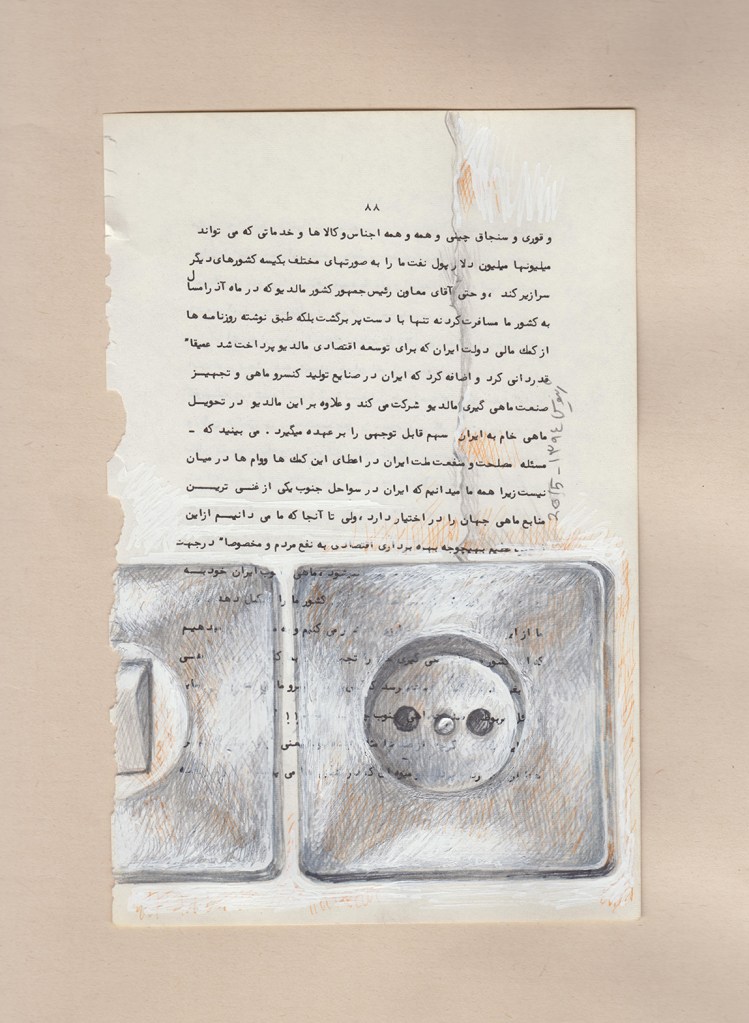

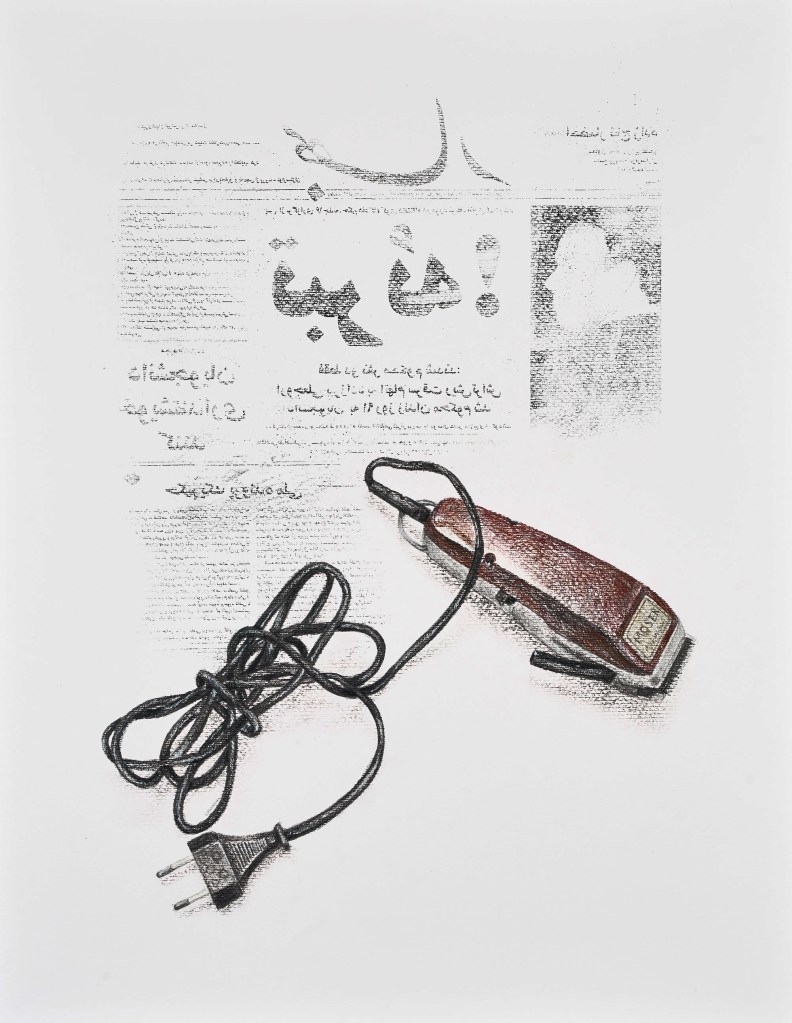

Materials such as anatomy textbooks, old newspapers, and political writings become surfaces for intervention. One drawing series uses Letters from Prison by Sadr Haj Seyed Javadi—a text from pre-revolutionary Iran that forms part of a collective memory many would prefer to forget. By juxtaposing ideological reflections with images of the body—nerves, hearts, bones—the artist links abstract ideas to the tangible structure of lived experience: blood, skin, organs, and decay.

Upon entering the gallery building, visitors encountered a sound installation playing a

historic audio clip on loop:

“Hello, hello, this is Tehran!”

This was the first broadcast aired on Iranian radio after the coup of August 19, 1953.

5-second audio file from Seyed Mehdi Mirashrafi’s national radio broadcast in the first hours of the coup on 19 August 1953

• Hello, hello, this is Tehran

Hello, hello, this is Tehran

People!

Great news!

Great News!

In a few minutes, General Zahedi, the prime minister, will read you a message from the Shah Citizens! The traitor Mossadeq has escaped! Today, the traitor Mossadeq was gunned down, thousands of people in the streets of Tehran! Citizens! This is Mirashrafi, a deputy of the national council speaking to you and Ette’laat at Kayhan and … newspapers

Today in Tehran, people revolted and burned down Mossadeq’s house

They have torn the followers of Imam Hossein into pieces

Passing through this sonic threshold, the viewer entered the exhibition—but instead of a wall text naming the artist, a scene from the film The Loneliness of the Long-Distance Runner was projected: the penultimate moment in which the main character, just steps away from the finish line, deliberately stops running and lets others win. A gesture of refusal, mistrust, and quiet resistance.

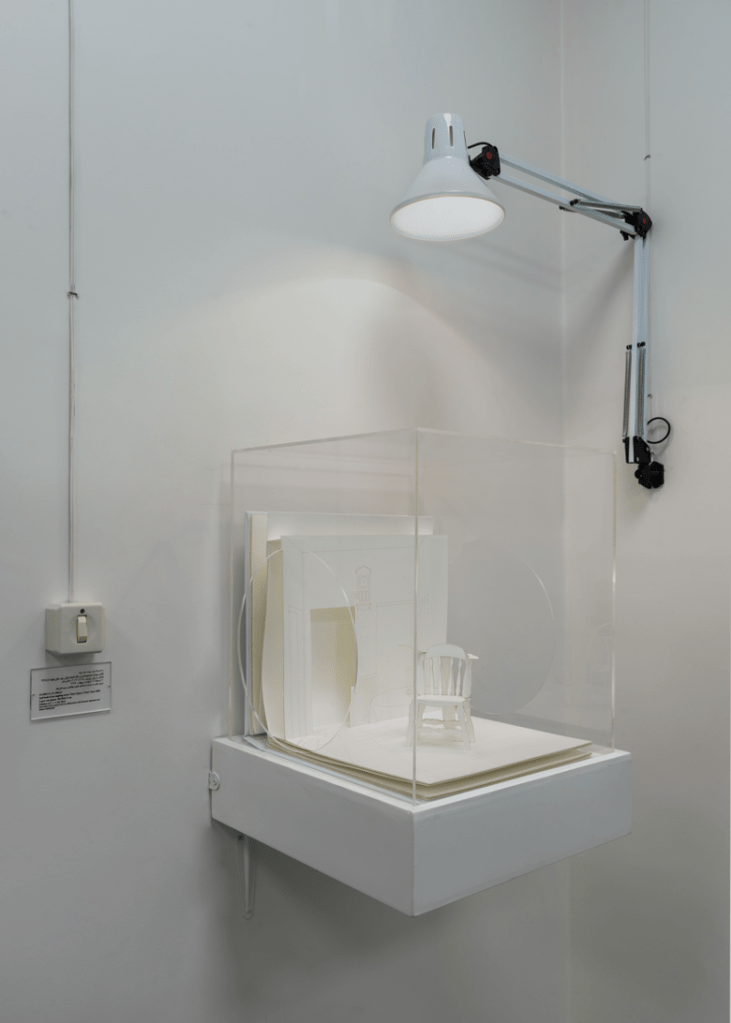

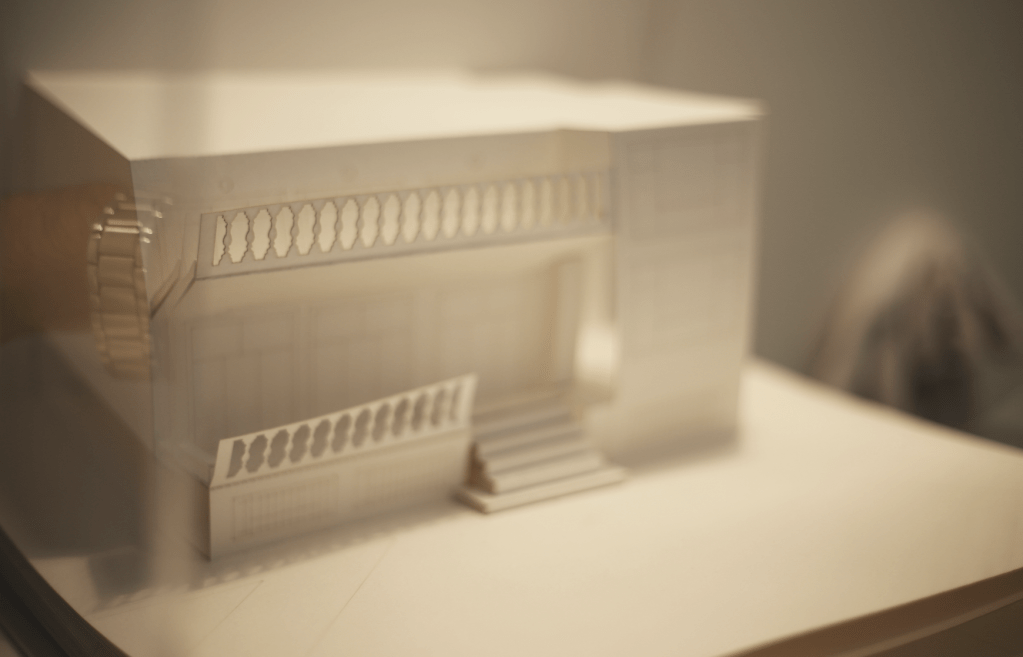

In the first exhibition room, a white pop-up book was displayed inside a vitrine. With each turned page, the three-dimensional interior of the home of Dariush and Parvaneh Forouhar unfolded—a reconstruction of the place where the two political dissidents were assassinated during Iran’s chain murders of the 1990s. The book revealed not just a house, but a site of surveillance, struggle, and death—layer by layer.

Nearby, another vitrine presented archival materials and press clippings about Dalal al-Mughrabi, the controversial Palestinian fighter who is considered a hero by many Palestinians and a terrorist by the Israeli state. Al-Mughrabi, a member of a secular liberation movement, along with her comrades, declared the first (albeit temporary) independent Palestinian republic inside a hijacked bus—an autonomous act that lasted only four hours, but remains deeply symbolic. Next to that, a video performance by the artist played silently. Recorded on the sixth anniversary of the silent protest of Iran’s Green Movement, it shows her riding a city bus from Enghelab (Revolution) Street to Azadi (Freedom) Square. In her hands is a small bus model. At the end of the journey, she softly sings an unofficial anthem—one that was never chosen as Iran’s national anthem, yet continues to carry the hopes of those yearning for freedom and dignity.

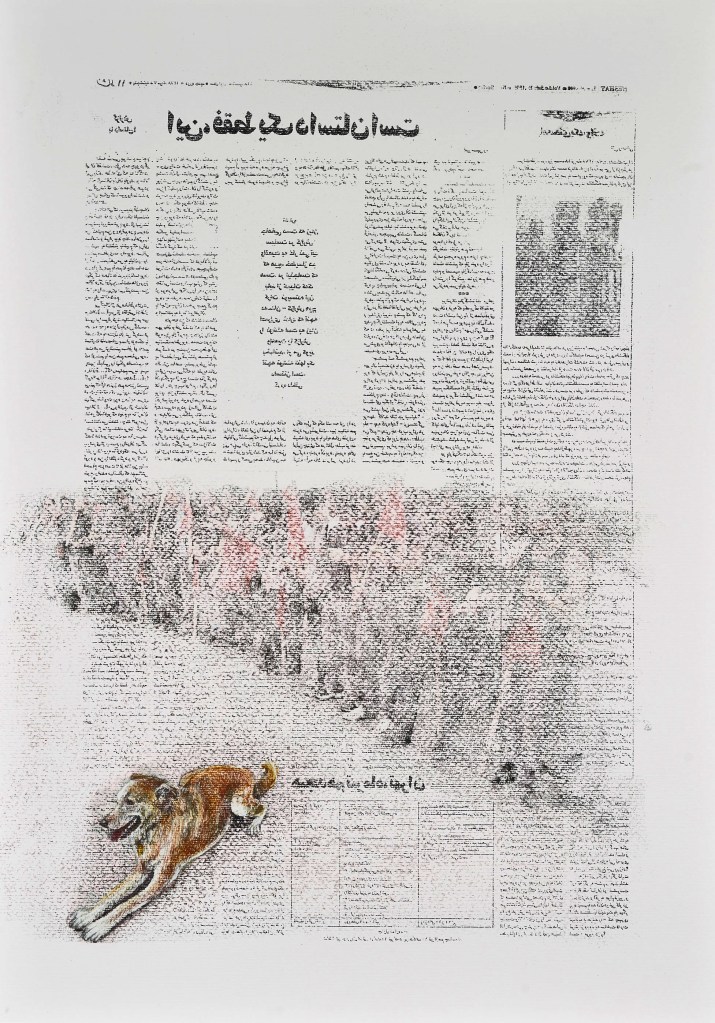

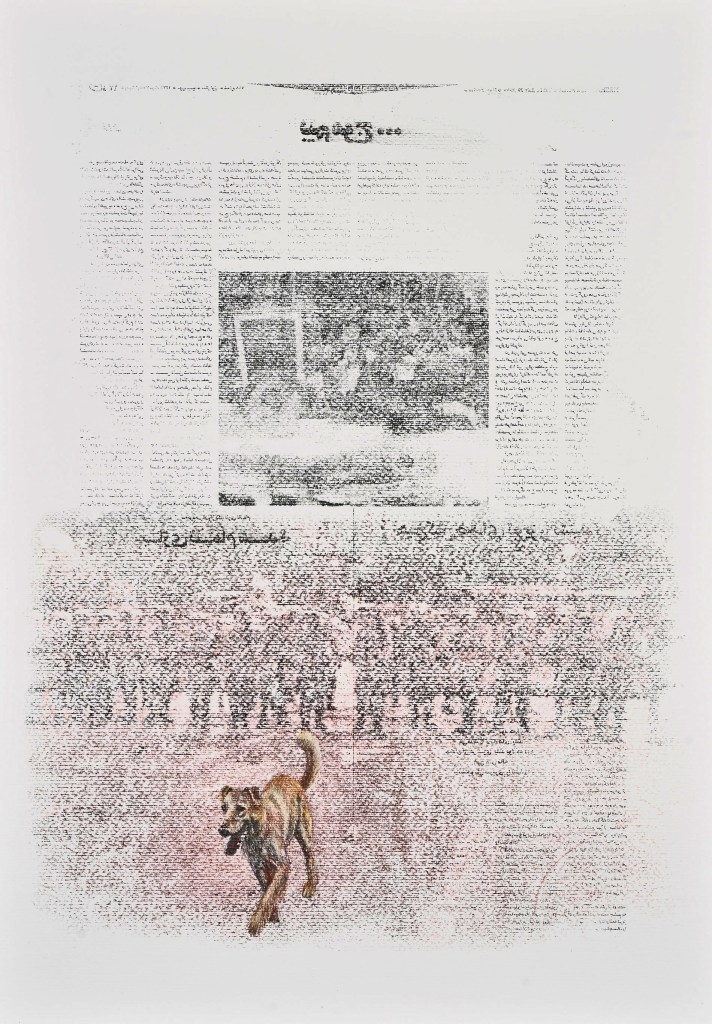

Another set of drawings in the same room—connected through cables—depicted the Riot Dogs of Greece. These street dogs became iconic during periods of protest for consistently appearing on the side of demonstrators. Rendered atop transfer prints of newspapers from Iran’s 1999 student movement, the drawings created a dialogue between two instinctive rebellions: the dog that intuitively knows which side to stand with, and the people who rise up under pressure.

In the same space, a sound piece echoed softly—a woman’s voice (the artist’s own) calmly counting numbers in an extended sequence. A recitation both obsessive and meditative, suggesting accumulation, record-keeping, or perhaps a silent inventory of loss.

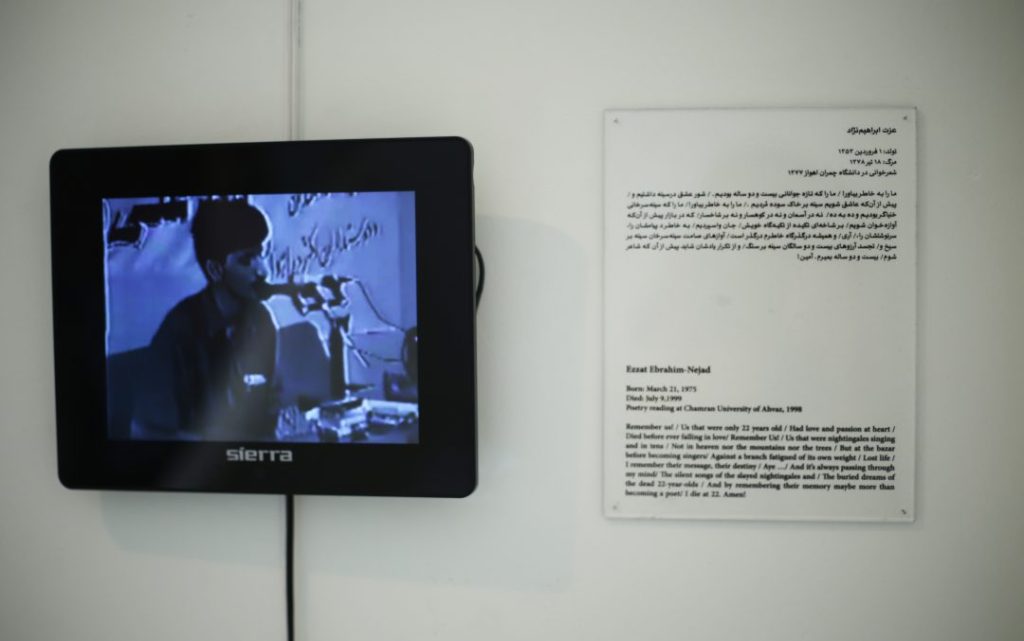

On the stairway leading to the second floor, a short video played: footage of one of the students killed during the 1999 dormitory attack in Tehran, reciting a poem: “Remember us…!”

A few steps later, a scene from The Beehive (Beehive, 1975), directed by Fereydoun Goleh, appeared—its protagonist, exhausted and enraged, smashing everything around him in a final act of desperate revolt.

Further along the corridor, a small monitor displayed a black-and-white sequence from the 1953 version of Titanic, showing the ship’s musicians calmly playing on deck as the vessel sinks. A quiet, futile gesture of grace in the face of collective disaster.

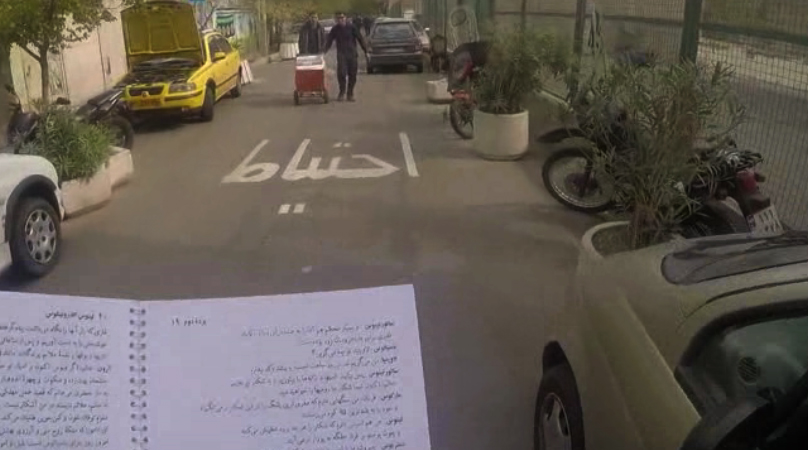

On the landing of the second floor, a three-hour video titled Reading Titus Andronicus was playing. In this piece, Jinoos Taghizadeh walks through various public and symbolic spaces in Tehran—including a cemetery, the Iranian parliament, and Theater Shahr—wearing a GoPro camera on her head, reading aloud from Shakespeare’s blood-soaked tragedy Titus Andronicus. The violent language echoes through places already charged with history and collective trauma.

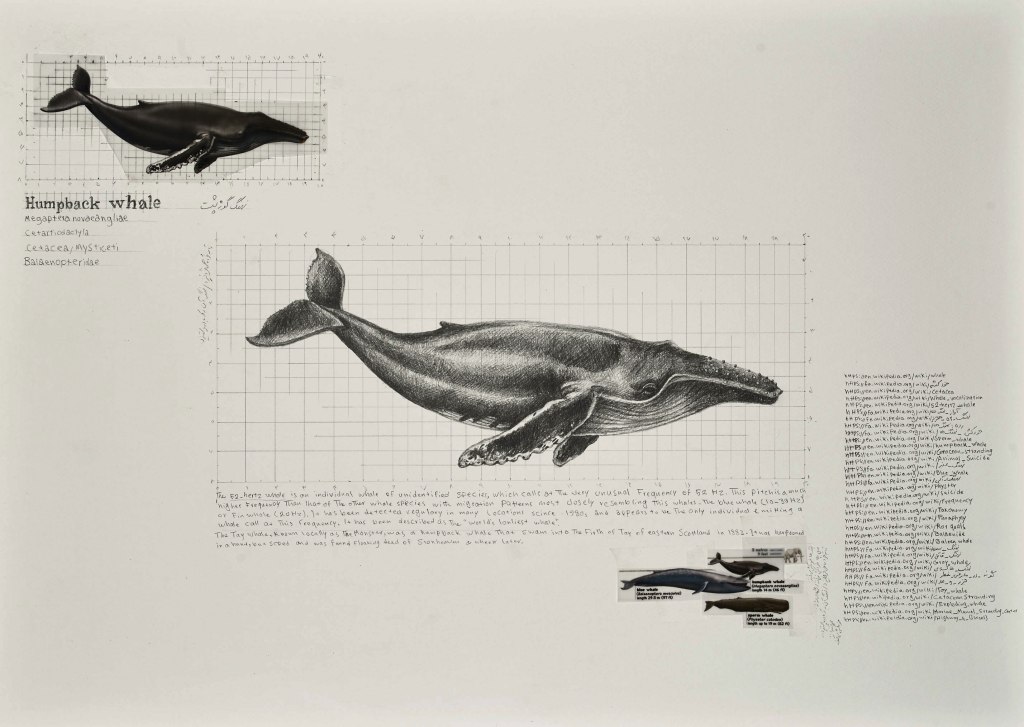

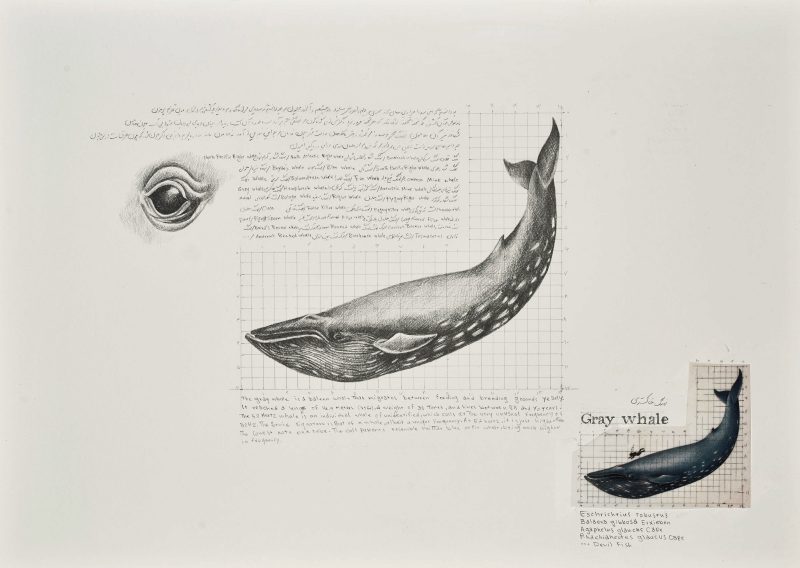

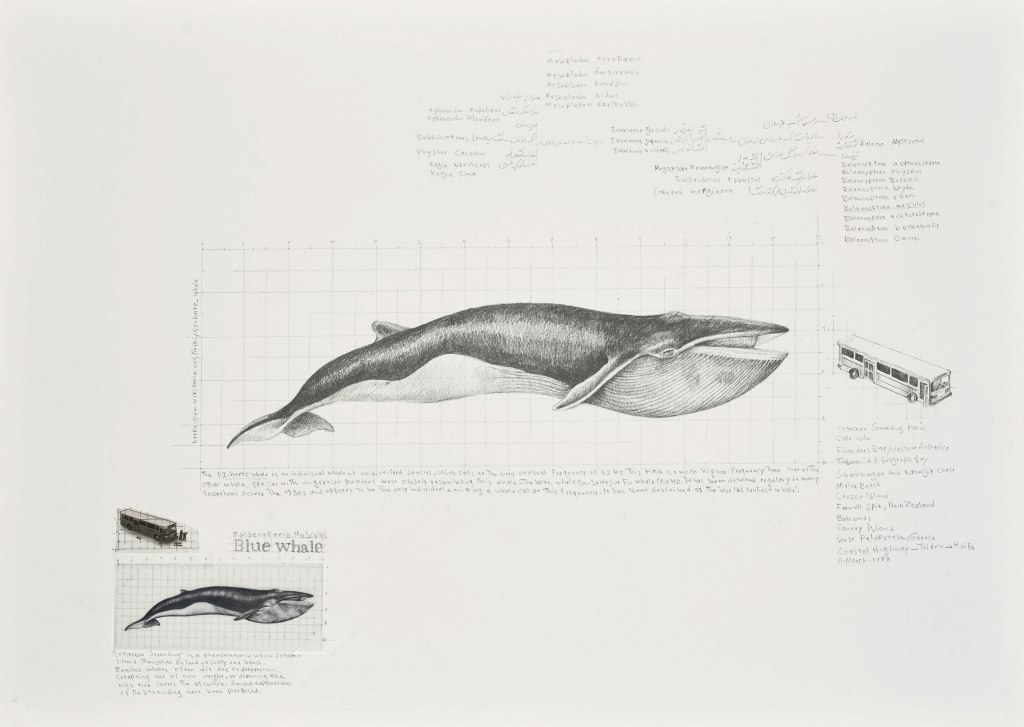

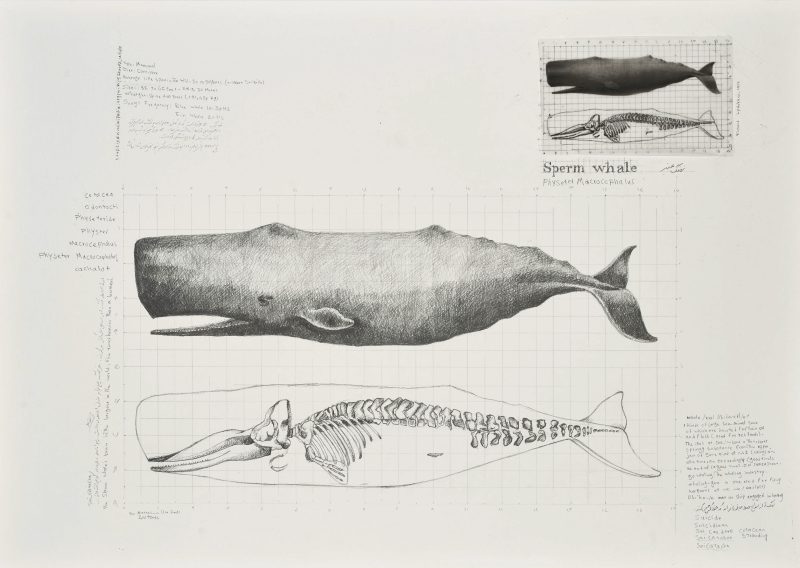

Next to this video, a series of drawings tell the story of the “52-hertz whale”—a solitary whale known for its unique frequency that no other whale can hear. Often called the loneliest whale in the world, it has roamed the oceans for decades, unheard. The wall features a hand-drawn map tracing the whale’s path across oceans over twenty years. Framed illustrations nearby compare the scale of various whale species to a city bus—an intersection of anatomy, distance, and displacement.

At the entrance of the second-floor hall, a short video excerpt from the final scene of They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? (dir. Sydney Pollack) is projected. One of the characters, after enduring a grueling marathon dance competition, quietly asks the other to help them end their life. A request made without drama—just fatigue, and surrender.

On another monitor, a nine-minute scene from Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia plays. The main character walks slowly across a dried fountain, trying to carry a lit candle from one side to the other, shielding the flame from the wind. A quiet, absurd, and almost sacred act of endurance.

In another corner of the second floor, the 3-minute video Proliferation (2013) plays in a quiet loop. A plastic blue rabbit and a woman with blue hair engage in a silent, mysterious exchange. The rabbit appears to say something; the woman seems to agree. Their images begin to multiply—duplicated two times, then three, then more—filling the frame as the background colors slowly shift. The dialogue remains unreadable, but something has clearly been accepted.

From here, the viewer exits through a terrace leading down to the gallery’s basement floor. This level houses a final installation featuring silkscreen posters, sculptures displayed in vitrines, and a video titled Production Line (2015).

Production Line is a 12-minute video in the format of a pseudo-documentary. It follows the manufacturing process of a work of art—from raw material to presentation. The specific artwork it documents is a piece titled Golden Dog Shit. The camera tracks the fabrication with dry seriousness, mimicking the language of factory documentaries and art production videos, blurring the line between critique and parody.

Open Wiring is also self-reflective. Some pieces act as internal critiques—of the artist’s own role as activist, of the fragility of artistic systems, and of the failure of long-term collective visions. It speaks to a political condition where urgency overrides planning, and the need to survive eclipses the ability to build. In the vitrines and on velvet-covered platforms are sculptural versions of the same object: dog feces, cast in gold, silver, and bronze. Carefully lit, neatly displayed, and presented like precious artifacts, the works raise questions about value, repetition, art labor, and the glorification of waste. As visitors exit the exhibition, the artist’s name finally appears—accompanied once again by the looping voice from the gallery entrance:

“Hello, hello, this is Tehran!”

The result is not a unified statement, but a charged field of associations—fragile, open-ended, and exposed. A space where meaning flows along visible lines, yet remains unstable, flickering, always at risk of overload.